As Dobermans, Dictator and Storm were in a class by themselves. No others were shown so few times and made such an impact on the public. They were not famous as Dobermans, they were famous as great dogs. In a breed never favored by enthusiasm from the publicity media, they were ambassadors of good will, each outstanding in his own era, first the red then the black.

Dictator dominated the 40’s as Storm dominated the 50’s.

They were retired from competition in their third year, and died in their tenth. Both were royally bred, each acquired as puppies for very little; Dictator for $150, Storm for the cost of his transportation. Storm was a Sagittarius and born lucky, the only male to survive in his litter and to have number 13 bring him luck for the rest of his life. Dictator was a Leo and really not lucky, not even to the end of his life.

Storm was bred by Rancho Dobe in California, and died in the East. Dictator was bred by Glenhugel in the East and died in California. They were never shown in California, although their owners were really Westerners. Storm’s owner was a breeder and judge before he was shown, but did little Doberman breeding thereafter; Dictator’s owner became a breeder and judge after his show career, and has continued in both capacities ever since.

Ridiculous stories were invented about both of them regarding the vast quantity of puppies they had sired. This happened not only in their lifetime, but even until the present day. Neither dog carried the dilution factor, nor did their black descendant, Top Skipper.

Dictator’s owner was the breeder of the first litter sired by Storm. The dam of the litter was Damasyn Sikhandi, Dictator’s daughter out of his granddaughter. When Storm won the Garden, the puppies were six months old. In two months, Dictator would be dead, and with him, their 3-year old dam. One of the puppies, Damasyn the Easter Bonnet, would later produce Top Skipper.

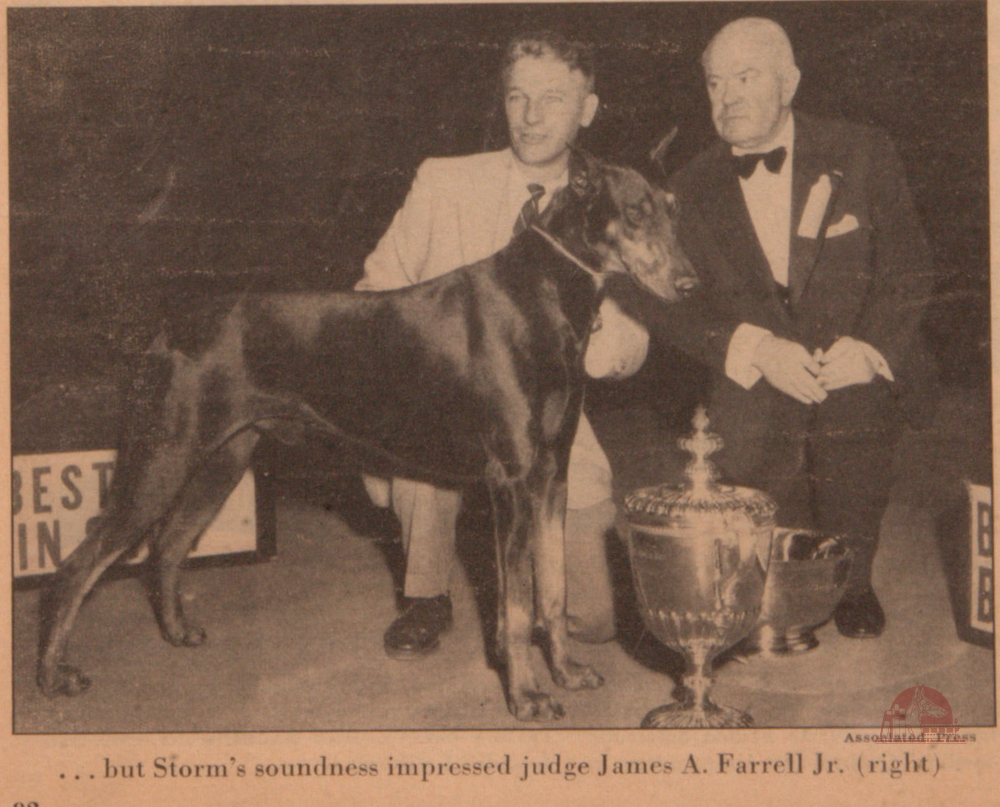

Neither dog was ever campaigned, and their show careers were very short with Dictator shown eighteen times and Storm twenty-five. Dictator achieved national fame when he won the Cleveland Classic at two and a half, retiring 11 months and 14 shows later when he won the Working Group at Westminster. Storm achieved national fame when he won Westminster at the age of two, retiring 14 shows later when he repeated the win at the age of three. Dictator was shown under specialty judges and all-rounders. Storm was shown under all-rounders, except for one breed specialist. Storm’s prime contender in reaching the top spot was Bangaway, the Boxer; Dictator’s were two Boxers, El Wendie and Warlord.

In the brilliance and brevity of their show careers, the two stand alone in American Doberman history. Each, during his lifetime, captured the imagination of the press, the adulation of the public, and the admiration and respect of those in other breeds, including the judges.

They were always good copy. When Ferry, the black German import, had won the Garden in 1939, the judge who awarded the win was quoted: “The only thing I didn’t like about him was that I couldn’t touch the devil.” To a press, whose opinion of Dobermans was based on this sort of publicity, the friendly red American-bred was a contrast and a happy discovery.

The country was at war. The male half of Dictator’s ownership was a Marine Captain on active duty and never present. The female half, in the eyes of reporters (who never read dog magazines) was an ingénue with a nice pet given to her by her husband as a Christmas present and discovered by experts to be a pot of gold. Dictator was piloted to his victories by an unassuming man in a blue serge suit (his breeder) or his mistress who, as one reporter put it, “seemed so all alone out there against those men professionals.”

Well, there was nothing professional about Dictator’s show career or any other aspect of his life. Professional handlers kept their dogs in crates in order to keep them fresh and sparkling for the finals. Though never unattended, Dictator was on a show bench, literally smothered by an adoring public. He ate it up. But by the time of Best-in-Show judging, it was a sheer miracle that he had anything of himself left to give. This, in fact, was his undoing at Westminster, on the final show of his career.

He was three and a half, in prime condition, and the reporters were so sure he would be the winner that Life Magazine spent the afternoon photographing a judging series with Anton Rost the judge and Tator the model. A professional could have insulated him against the public and photographers. Well-intentioned though they were, their demands were insatiable.

By the late hours, of that second day, I knew that only a miracle could help us. The greatest dogs in the country would be in the final competition, but I had heard that a spunky newcomer had fought his way into the charmed circle. He alone could provide that miracle if I could just get near him when we first came into the ring. A snappy challenge from the fiery Scottie would be the life-giving injection Tator needed.

But destiny was to thwart us, as she did on many occasions. The clock was nearing eleven as Tator and I waited downstairs on the bench by ourselves. Everyone else had gone home, or upstairs to watch the judging. I didn’t realize the loudspeaker system did not include the basement where the dogs were benched.

Suddenly, there was Dick Webster, who had so often been our good fairy. He had been running and was out of breath. “You’re supposed to be up in the ring. Hurry, they’ve been calling for you and the judging has already begun. Van Meter isn’t there either, “I pulled Tator off the bench, snapping the leash on him as we ran the long way up into the big ring.

The dogs were set up and partially judged. The Scottie, already gaited, was minding his own business, eyes glued to his handler in perfect decorum, I knew immediately that there would be no miracle. We had arrived too late and all was lost. When the dramatic announcement was made that the Office of Defense Transportation had banned the big sporting events for the Duration, I decided that I would never show Dictator again. It was too nerve wracking, not for him, but for me.

The Life Magazine people were sympathetic, as indeed they should have been, for I had been reluctant about the pictures they had planned to run. In their issue covering Westminster, the only finalists they showed were the triumphant Scottie, and underneath, a big picture of Tator with the caption: Sentimental favorite was the Doberman, given by a Marine Captain as a Christmas present to his wife.”

The next day, Dictator received as much publicity as the result of not winning as the winner himself. Well, thought I, such are the fortunes of war, we can never look backward.

Dictator, throughout his lifetime, was as nonprofessional as could be conceived. He didn’t even have a stud card. The only movies of him were made, not in his prime but at the age of nine. They were done by Curt Sloan to illustrate McDowell Lyon’s lectures on his theories of what really was correct gait.

Everything about Storm, on the other hand, was smoothly professional. His owner was an advertising executive of one of the best New York agencies in the business – Batton , Barton, Durstine and Osborn, the famous “BBD&O.” In the publicity, the movies made of him, Len Carey’s fine hand could be seen everywhere. Except on one occasion, when he handled him himself under Mrs. Dodge, Storm was always handled by the top professional in Dobermans, A. Peter Knoop.

Comparing the two dogs is like comparing home movies to a Hollywood production. Storm was a handler’s dream. Dictator was an exhibitor’s nightmare. No dog could compare with him when he saw something that attracted his attention, but this happy circumstance could never be counted on, not foreseen, at least by me. Years later, Nate Levine would offer to campaign him for me without charge, saying that he had never really been seen, that a novice could handle a dog in a showing mood, but it took a professional to keep him showing when he wasn’t. However, Storm’s showmanship could be turned on as easily as water from a faucet, a quality he inherited from Jockel von Burgund, rather than Jessy, as had so often been stated.

They were of totally different breeding, but I have spent the years trying to combine and consolidate the best of both. They were two great dogs, the like of which is rarely seen in any breed, each making a tremendous contribution to the prestige of the American Doberman.